|

Wall Street Banksters Feeling Heat

by red Thursday, May 10 2012, 11:59pm

international /

imperialism /

commentary

Jail 'em for Fraud and Manipulating Commodities Markets

Deserving of all the contempt and hostility the public directs at criminal Wall St Banksters, JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs etc., chief honcho of JP Morgan, Jamie Dimon, openly apologised for wrong doings – “self inflicted mistakes” (O, really!) -- and admitted that certain practices the Bank engaged in were unprincipled – understatement of the year!

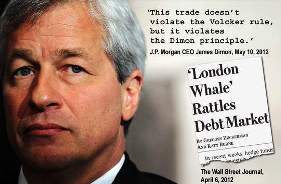

Jamie Dimon, rogue Bankster

Never mind the fact that not a cent of personal executive spoils has ever been returned to the public in a gesture of good faith, or the ($) trillions in odorous profits and taxpayer BAILOUTS that remains in bank coffers, Dimon says 'sorry!' Well, blow it out your arse, the breath you feel on your stinking Jew neck is mine and the nightmares you have of lynch mobs stringing up Wall Street Bankers are prophetic -- If you can’t see it coming you’re as BLIND as you are GREEDY!

How dare you [Dimon] make hot air apologies without any attempt at RESTITUTION/REPAYMENT of the trillions in misappropriated funds and losses, you filthy, thieving, slime bag -- TAKE RESPONSIBILITY and PAY! Tell it to your Jew mates at Goldman Sachs, your time is coming to an E-N-D!

Read the following piece from the WSJ and pay particular attention to the roulette, gambling LANGUAGE these rogues use. We work HARD for every cent and they BET in billions of OUR dollars. Banking and Finance sectors MUST be tightly regulated in order to protect the interests of the public and protect the GLOBAL economy, that is OBVIOUS, puppet Obama:

J.P. Morgan's $2 Billion Blunder

A massive trading bet boomeranged on J.P. Morgan Chase JPM +0.25% & Co., leaving the bank with at least $2 billion in trading losses and its chief executive, James Dimon, with a rare black eye following a long run as what some called the "King of Wall Street."

The losses stemmed from wagers gone wrong in the bank's Chief Investment Office, which manages risk for the New York company. The Wall Street Journal reported early last month that large positions taken in that office by a trader nicknamed "the London whale" had roiled a sector of the debt markets.

The bank, betting on a continued economic recovery with a complex web of trades tied to the values of corporate bonds, was hit hard when prices moved against it starting last month, causing losses in many of its derivatives positions. The losses occurred while J.P. Morgan tried to scale back that trade.

The bank's strategy was "flawed, complex, poorly reviewed, poorly executed and poorly monitored," Mr. Dimon said Thursday in a hastily arranged conference call with analysts and investors after the stock-market close. He called the mistake "egregious, self-inflicted," and said: "We will admit it, we will fix it and move on," he said.

The trading loss "plays right into the hands of a whole bunch of pundits out there," Mr. Dimon said. "We will have to deal with that—that's life."

Asked about the Volcker rule, he said, "This doesn't violate the Volcker rule, but it violates the Dimon principle."

J.P. Morgan shares fell about 6.5% to $38.09 in after-hours trading. Citigroup C +0.66% was off about 3.6%, SunTrust STI +2.21% 3.3%, Fifth Third Bancorp 2.7%,

Bank of America BAC -0.39% 2.6%, Morgan Stanley MS +0.71% 2.5% and Goldman Sachs GS -0.90% 2.4%.

J.P. Morgan, the nation's largest bank by assets, said in its quarterly filing with regulators Thursday that the plan it has been using to hedge risks "has proven to be riskier, more volatile and less effective as an economic hedge than the firm previously believed."

It slashed its estimate for the unit that houses the Chief Investment Office to $800 million in second-quarter losses from a previous estimate of $200 million in profits. Mr. Dimon said the trading losses were "slightly more" than $2 billion so far in the second quarter.

A person close to the bank said the current loss is actually $2.3 billion.

The losses have been offset by about $1 billion in gains on securities sales. Mr. Dimon said "volatility" in markets could cost the bank an additional $1 billion this quarter.

The Journal reported in April that hedge funds and other investors were making bets in the market for insurance-like products called credit-default swaps, or CDS, to try to take advantage of trades done by a London-based trader named Bruno Michel Iksil who worked out of the Chief Investment Office, or CIO.

Mr. Dimon said on the company's first-quarter earnings call April 13 that questions about the office's trading were "a complete tempest in a teapot." The CEO didn't learn of the full extent of the losses until after that earnings call on April 13, said a person familiar with the situation.

On Thursday he admitted the bank acted "defensively" when news reports surfaced. "With hindsight we should have been paying more attention to it," he said. "This not how we want to run a business."

Mr. Iksil is still at the bank, said people close to the bank. He didn't respond to an email requesting comment.

People within the CIO group, which has been under the radar at J.P. Morgan and not well understood by analysts following the company, were long aware Mr. Iksil had built derivative positions with a face value of $100 billion or more.

Mr. Dimon was regularly briefed on details of some of the group's positions, according to several people close to the matter, suggesting he too overlooked the potential risks of the trade.

The CIO group once had a large trade designed to protect the company from a downturn in the economy. Earlier this year, it began reducing that position and take a bullish stance on the financial health of certain companies and selling protection that would compensate buyers if those companies defaulted on debts.

Mr. Iksil was a heavy seller of CDS contracts tied to a basket, or index, of companies. In April the cost of protection began to rise, contributing to the losses.

Mr. Iksil's group had roughly $350 billion of investment securities at Dec. 31, according to company filings, or about 15% of the bank's total assets.

J.P. Morgan's investment bank's "value-at-risk," a measure of how much money it stands to lose on a given day, nearly doubled in the first quarter, according to the filing Thursday. It rose to an average of $170 million from $88 million a year earlier.

Risk-taking was driven largely by positions taken in the CIO group, said the company. The value-at-risk for that division averaged $129 million in the first quarter, more than double a year earlier. The bank attributed the jump to "changes in the synthetic credit portfolio held by CIO."

"This is yet another example of the need for the more than $700 trillion derivatives market to be brought into the light of financial regulation," said Dennis Kelleher, president of Better Markets, a liberal nonprofit focused on financial reform.

The losses could potentially expose bank employees to so-called clawback policies that permit the recovery of compensation in the event of a financial restatement. Banks like J.P. Morgan have adopted such policies, which also are required under the Dodd-Frank financial overhaul law.

Mr. Dimon said the bank has an extensive review under way of what went wrong, which he said included "many errors," "sloppiness" and "bad judgment."

Asked what, in hindsight, he should have paid more attention to, Mr. Dimon deadpanned: "newspapers."

© 2012 Dow Jones & Company, Inc

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304070304577396511420792008.html COMMENTS show latest comments first show comment titles only

jump to comment 1

Released Documents Show How Goldman Sachs Engaged in 'Naked Short Selling'

by Matt Taibbi via burmese - Rolling Stone Wednesday, May 16 2012, 8:20am

Though legal justice is glaringly absent from our legal system poetic justice continues to reign supreme. Lawyers for Goldman Sachs inadvertently release some of the Bank’s darkest, most compromising secrets into the public domain.

The lawyers for Goldman and Bank of America/Merrill Lynch have been involved in a legal battle for some time – primarily with the retail giant Overstock.com, but also with Rolling Stone, the Economist, Bloomberg, and the New York Times. The banks have been fighting us to keep sealed certain documents that surfaced in the discovery process of an ultimately unsuccessful lawsuit filed by Overstock against the banks.

Last week, in response to an Overstock.com motion to unseal certain documents, the banks’ lawyers, apparently accidentally, filed an unredacted version of Overstock’s motion as an exhibit in their declaration of opposition to that motion. In doing so, they inadvertently entered into the public record a sort of greatest-hits selection of the very material they’ve been fighting for years to keep sealed.

I contacted Morgan Lewis, the firm that represents Goldman in this matter, earlier today, but they haven’t commented as of yet. I wonder if the poor lawyer who FUBARred this thing has already had his organs harvested; his panic is almost palpable in the air. It is both terrible and hilarious to contemplate. The bank has spent a fortune in legal fees trying to keep this material out of the public eye, and here one of their own lawyers goes and dumps it out on the street.

The lawsuit between Overstock and the banks concerned a phenomenon called naked short-selling, a kind of high-finance counterfeiting that, especially prior to the introduction of new regulations in 2008, short-sellers could use to artificially depress the value of the stocks they’ve bet against. The subject of naked short-selling is a) highly technical, and b) very controversial on Wall Street, with many pundits in the financial press for years treating the phenomenon as the stuff of myths and conspiracy theories.

Now, however, through the magic of this unredacted document, the public will be able to see for itself what the banks’ attitudes are not just toward the “mythical” practice of naked short selling (hint: they volubly confess to the activity, in writing), but toward regulations and laws in general.

“Fuck the compliance area – procedures, schmecedures,” chirps Peter Melz, former president of Merrill Lynch Professional Clearing Corp. (a.k.a. Merrill Pro), when a subordinate worries about the company failing to comply with the rules governing short sales.

We also find out here how Wall Street professionals manipulated public opinion by buying off and/or intimidating experts in their respective fields. In one email made public in this document, a lobbyist for SIFMA, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, tells a Goldman executive how to engage an expert who otherwise would go work for “our more powerful enemies,” i.e. would work with Overstock on the company’s lawsuit.

“He should be someone we can work with, especially if he sees that cooperation results in resources, both data and funding,” the lobbyist writes, “while resistance results in isolation.”

There are even more troubling passages, some of which should raise a few eyebrows, in light of former Goldman executive Greg Smith's recent public resignation, in which he complained that the firm routinely screwed its own clients and denigrated them (by calling them "Muppets," among other things).

Here, the plaintiff’s motion refers to an “exhibit 96,” which refers to “an email from [Goldman executive] John Masterson that sends nonpublic data concerning customer short positions in Overstock and four other hard-to-borrow stocks to Maverick Capital, a large hedge fund that sells stocks short.”

Was Goldman really disclosing “nonpublic data concerning customer short positions” to its big hedge fund clients? That would be something its smaller, “Muppet” customers would probably want to hear about.

When I contacted Goldman and asked if it was true that Masterson had shared nonpublic customer information with a big hedge fund client, their spokesperson Michael Duvally offered this explanation:

Among other services it provides, Securities Lending at Goldman provides market color information to clients regarding various activity in the securities lending marketplace on a security specific or sector specific basis. In accordance with the group's guidelines concerning the provision of market color, Mr. Masterson provided a client with certain aggregate information regarding short balances in certain securities. The information did not contain reference to any particular clients' short positions.

You can draw your own conclusions from that answer, but it's safe to say we'd like to hear more about these practices.

Anyway, the document is full of other interesting disclosures. Among the more compelling is the specter of executives from numerous companies admitting openly to engaging in naked short selling, a practice that, again, was often dismissed as mythical or unimportant.

A quick primer on what naked short selling is. First of all, short selling, which is a completely legal and even beneficial activity, is when an investor bets that the value of a stock will decline. You do this by first borrowing and then selling the stock at its current price, then returning the stock to your original lender after the price has gone down. You then earn a profit on the difference between the original price and the new, lower price.

What matters here is the technical issue of how you borrow the stock. Typically, if you’re a hedge fund and you want to short a company, you go to some big-shot investment bank like Goldman or Morgan Stanley and place the order. They then go out into the world, find the shares of the stock you want to short, borrow them for you, then physically settle the trade later.

But sometimes it’s not easy to find those shares to borrow. Sometimes the shares are controlled by investors who might have no interest in lending them out. Sometimes there’s such scarcity of borrowable shares that banks/brokers like Goldman have to pay a fee just to borrow the stock.

These hard-to-borrow stocks, stocks that cost money to borrow, are called negative rebate stocks. In some cases, these negative rebate stocks cost so much just to borrow that a short-seller would need to see a real price drop of 35 percent in the stock just to break even. So how do you short a stock when you can’t find shares to borrow? Well, one solution is, you don’t even bother to borrow them. And then, when the trade is done, you don’t bother to deliver them. You just do the trade anyway without physically locating the stock.

Thus in this document we have another former Merrill Pro president, Thomas Tranfaglia, saying in a 2005 email: “We are NOT borrowing negatives… I have made that clear from the beginning. Why would we want to borrow them? We want to fail them.”

Trafaglia, in other words, didn’t want to bother paying the high cost of borrowing “negative rebate” stocks. Instead, he preferred to just sell stock he didn’t actually possess. That is what is meant by, “We want to fail them.” Trafaglia was talking about creating “fails” or “failed trades,” which is what happens when you don’t actually locate and borrow the stock within the time the law allows for trades to be settled.

If this sounds complicated, just focus on this: naked short selling, in essence, is selling stock you do not have. If you don’t have to actually locate and borrow stock before you short it, you’re creating an artificial supply of stock shares.

In this case, that resulted in absurdities like the following disclosure in this document, in which a Goldman executive admits in a 2006 email that just a little bit too much trading in Overstock was going on: “Two months ago 107% of the floating was short!”

In other words, 107% of all Overstock shares available for trade were short – a physical impossibility, unless someone was somehow creating artificial supply in the stock.

Goldman clearly knew there was a discrepancy between what it was telling regulators, and what it was actually doing. “We have to be careful not to link locates to fails [because] we have told the regulators we can’t,” one executive is quoted as saying, in the document.

One of the companies Goldman used to facilitate these trades was called SBA Trading, whose chief, Scott Arenstein, was fined $3.6 million in 2007 by the former American Stock Exchange for naked short selling.

The process of how banks circumvented federal clearing regulations is highly technical and incredibly difficult to follow. These companies were using obscure loopholes in regulations that allowed them to short companies by trading in shadows, or echoes, of real shares in their stock. They manipulated rules to avoid having to disclose these “failed” trades to regulators.

How they did this is ingenious, elaborate, and complex, and we’ll get into it more at a later date. In the meantime, this document all by itself shows numerous executives from companies like Goldman Sachs Execution and Clearing (GSEC) and Merrill Pro talking about a conscious strategy of “failing” trades – in other words, not bothering to locate, borrow, and deliver stock within the time alotted for legal settlement. For instance, in one email, GSEC tells a client, Wolverine Trading, “We will let you fail.”

More damning is an email from a Goldman, Sachs hedge fund client, who remarked that when wanting to “short an impossible name and fully expecting not to receive it” he would then be “shocked to learn that [Goldman’s representative] could get it for us.”

Meaning: when an experienced hedge funder wanted to trade a very hard-to-find stock, he was continually surprised to find that Goldman, magically, could locate the stock. Obviously, it is not hard to locate a stock if you’re just saying you located it, without really doing it.

As a hilarious side-note: when I contacted Goldman about this story, they couldn't resist using their usual P.R. playbook. In this case, Goldman hastened to point out that Overstock lost this lawsuit (it was dismissed because of a jurisdictional issue), and then had this to say about Overstock:

Overstock pursued the lawsuit as part of its longstanding self-described "Jihad" designed to distract attention from its own failure to meet its projected growth and profitability goals and the resulting sharp drop in its stock price during the 2005-2006 period.

Good old Goldman -- they can't answer any criticism without describing their critics as losers, conspiracy theorists, or, most frequently, both.

Anyway, this galactic screwup by usually-slick banker lawyers gives us a rare peek into the internal mindset of these companies, and their attitude toward regulations, the markets, even their own clients. The fact that they wanted to keep all of this information sealed is not surprising, since it’s incredibly embarrassing stuff, if you understand the context.

More to come: until then, here’s the motion, and pay particular attention to pages 14-19.

© 2012 Rolling Stone

Goldman Motion Goldman Motion

http://tinyurl.com/88buvl9

<< back to stories

|